The Barbizon School was an informal group of French painters that produced work in and around the village of Barbizon, which lies just outside of Paris close to the Forest of Fontainebleau. They were pioneers of the Naturalist movement in landscape art painting. Barbizon school is characterized by tonal qualities, colour harmony, loose brushwork, and gentleness of form. The Barbizon school operated roughly between 1830 and 1870. It derives its name from the French village of Barbizon, situated on the border of the Forest of Fontainebleau and served as a meeting place for numerous artists.

The Barbizon School was an informal group of French painters that produced work in and around the village of Barbizon, which lies just outside of Paris close to the Forest of Fontainebleau. They were pioneers of the Naturalist movement in landscape art painting. Barbizon school is characterized by tonal qualities, colour harmony, loose brushwork, and gentleness of form. The Barbizon school operated roughly between 1830 and 1870. It derives its name from the French village of Barbizon, situated on the border of the Forest of Fontainebleau and served as a meeting place for numerous artists.

Most Barbizon School painters such as From Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Charles Jacque, Jules Dupre, Jean-François Millet, Charles François Daubigny and Édouard Manet came from different backgrounds. These Impressionist painters, who adopted the Barbizon method of painting outdoors settings, would particularly value the new emphasis on realistic detail and away from the Neoclassical tradition that strove to replicate classical antiquity. They took a naturalistic approach to paint in response to the stylized and idealized representations of people and landscapes. Landscape paintings were used as a backdrop for idealized mythological, lyrical, or Biblical subjects rather than as a subject in its own right. They accurately captured what they saw, made careful observations, and painted directly from nature to accurately capture the hues and forms of the rural areas.

While many Barbizon painters painted landscapes with farmworkers and typical images of village life, landscape painting constituted the majority of their creative output. Members of the group came from various backgrounds. They painted in various styles, but their love of painting outdoors and their goal to make landscape painting more than just a backdrop for legendary or classical settings brought them together.

Works of art created by the Barbizon painters include Oak Trees at Bas-Bréau, Oak Trees and Pond, The Beech Tree, The Gleaners, and The Village of Gloton. They feature characters, but most of them lack a story, which matches the Barbizon School’s larger belief that the landscape should serve as the primary topic of art. The exception to this rule is the work of Millet, who applied the principles of Naturalism to the human form while concentrating on the agricultural laborers in the region around Barbizon and frequently included social commentary.

The Barbizon painters experimented with several techniques, such as applying wet paint on top of wet paint, finishing a canvas in one sitting, and focusing on how light affected the environment. Many artists also employed looser brushwork and a more free-form approach than was customary in Academic painting. These experiments profoundly influenced the Impressionists, who traveled to Barbizon as young artists to study with the School members.

History of Barbizon School

Beginnings – 1824

In the 18th century, French painters such as the Neoclassicists Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld, Théodore Caruelle d’Aligny, and Alexandre Desgoffe began to visit the Forest of Fontainebleau. The French myths and traditions associated with the forest also appealed to the painters and the wild and varied scenery.

Several prominent French artists, including Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix, praised three paintings by the English painter John Constable who exhibited them at the 1824 Salon de Paris, marking the beginnings of the Barbizon School. He stated of the response, “They are struck with [the paintings’] vivacity and freshness, qualities not present in their own work.” The Hay Wain became one of Constable’s most popular works, was awarded a Salon gold medal and relocated to a prominent position in the exhibition.

John Constable was acclaimed for his original method of creating art, which rejected the academic norm of emulating earlier works in favor of using observational studies of nature as his main inspiration. The uniqueness of Constable’s method would significantly impact the development of French art, especially among the Barbizon School’s members.

However, it was not until Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and Théodore Rousseau arrived in the region at the beginning of the 19th century that the region became a draw for artists like Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, Constant Troyon, Charles Jacque, and Narcisse-Virgilio Diáz de la Peña.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot started drawing and painting landscapes in and around Fontainebleau in the early 1820s. Even though he never truly settled there, he regularly visited, particularly in 1829 and 1830, and wa prominent and involved patron of fellow artists. Early in the 1830s, the construction of the Lyon railway system from Paris made it simple to get to Barbizon, and the opening of the Auberge Ganne, a new inn that gave artists a place to stay and work. The inn quickly developed into a meeting place for artists where they could connect, exchange ideas, and collaborate.

Rise and Development of Barbizon School- (1829- Late 1860s)

Theodore Rousseau began making extended trips to the French landscape of Fontainebleau in 1833. During these trips, he would explore the surroundings and paint and sketch outside. He was a natural leader of the Barbizon group because of his love of painting landscapes and forests, and other artists who joined him on painting outings were influenced by his methods and viewpoints. The village of Barbizon and its surroundings rose to prominence as a major art destination throughout the ensuing decades, particularly during the 1848 Revolutions, which forced many Parisian artists to flee to the relative safety of the countryside. Hundreds of paintings and pictures were produced during this period that portrayed the region and rural life.

The Barbizon painters’ work was not initially well received by critics and were rejected by the Salon; it wasn’t until the 1850s that they started to find success. The Salon between 1836 and 1841 rejected three paintings by Rousseau but were later ultimately admitted in 1849. From that point forward, Naturalism gained popularity, reflected in the 1855 Universal Exposition, where several Barbizon artists were displayed. Most received official Académie des Beaux-Arts recognition and began charging high fees for their paintings; their work peaked in popularity at the turn of the century. Others were less skilled, but certain Barbizon painters were masters of composition and description. Nevertheless, there is no denying their historical significance because they helped France’s establishment of pure, objective landscape painting as a respectable genre.

The Barbizon School helped other European artistic communities and associations to emerge beginning in the 1860s. While the landscape, rural life, and en Plein air painting drew the attention of the painters in each region, they also used various techniques, much like the Barbizon School. Some painters moved from one group to another, frequently to collaborate or be among particular creators.

End of Barbizon School

The art movement ended in the early 1870s when both Théodore Rousseau (1867) and Jean-François Millet (1875) died at Barbizon. Beginning in the 1860s, The Barbizon School inspired the creation of other associations of artists around Europe, including Pont-Aven, Concarneau, The Hague School, and the Newlyn School.

Characteristics of Barbizon School

The characteristics of Barbizon school include: tonal qualities, color, loose brushwork, and softness of form.

Tonal qualities

The Barbizon style is defined by its almost sole focus on the landscape and its direct study of nature while maintaining a realistic aesthetic with a little romantic undertone. They gave up the idyllic view of rural life and started to examine nature and how it is represented critically. This natural observation emotionally impacts the artist’s psyche and calls for solid tonal qualities so that the landscapes have a distinctly dramatic quality.

Loose brushwork

In contrast to traditional Academic painting, the Barbizon art movement embraced looser brushstrokes and a more free-form approach to design. The Impressionists, who traveled to Barbizon as young artists to study, were profoundly influenced by these experiments.

Color

Despite en Plein air, the Barbizon School creators finished their pieces in the studio. Because they employed Delacroix’s technique of juxtaposing bits of colour rather than fusing colours seamlessly to create teints, their paintings were sometimes criticized as “rough drafts.

Barbizon School Artists

Some of Barbizob painters included: Théodore Rousseau, Charles-François Daubigny, Jules Dupré, Constant Troyon and Charles Jacque. Most of their works were landscape paintings, but some also created genre scenes of village life and landscapes with farm workers. Their perseverance contributed to the transformation of landscape painting from a mere background of the Neoclassical style to a significant genre.

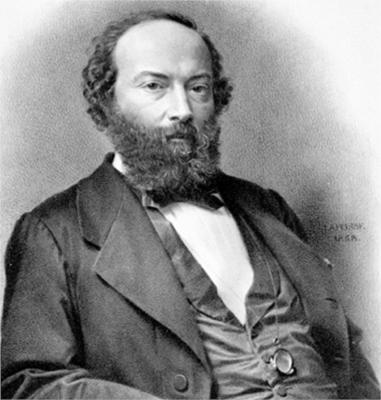

Théodore Rousseau

Born: April 15, 1812; Paris, France

Died: December 22, 1867; Barbizon , France

Nationality: French

Théodore Rousseau was renowned for his unique and outlandish paintings of nature. He was revered as the founder and de facto head of the Barbizon School of landscape painting. Rousseau was one of the first artists to have gone outside to examine and study natural forms, having discovered his passion for nature and his desire to convey it via landscape paintings early in life. Thus, he had chosen his subject in a way that finally enabled him to organize and run the Barbizon School. Rousseau transformed the landscape from merely background support to an independent entity by painting it for its own purpose. He would journey for days at a time into the woods, frequently leading and guiding other artists on outdoor painting excursions. Even while every one of his paintings was the result of direct empirical research into nature, he could infuse them with an incomparable poignancy that was singular – much like his signature.

In 1831, 1833, 1834, and 1835, he exhibited six pieces at the Salon, and in 1836, his masterpiece Paysage du Jura [La Descente des Vaches] was rejected by the Salon jury. Between 1836 and 1841, he submitted an additional eight paintings to the Salon, but none were accepted. Until 1849, when all three paintings were accepted, he halted sending work to the Salon. During these years of artistic exile, Rousseau produced some of his finest works: “The Chestnut Avenue,” “The Marsh in the Landes,” and “Hoar-Frost.”

After the reorganization of the Salon in 1848, he exhibited his masterpiece “The Edge of the Forest” in 1851. In the same year, while Narcisse Virgilio Diaz was appointed Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, Rousseau remained undecorated. However, he was shortly nominated and given the Cross. He would eventually attain the rank of Legion of Honor officer. At the Exposition Universelle of 1853, where all of Rousseau’s rejected paintings from the preceding two decades were presented, his works were among the finest of the many outstanding ensembles on display. However, following the unsuccessful auction of his works in 1861, he considered leaving Paris for Amsterdam, London, or perhaps New York.

Charles-François Daubigny

Born: 15 February 1817 Paris, France

Died: 19 February 1878 (aged 61) Paris, France

Nationality: French

French painter Charles-François Daubigny’s landscapes significantly influenced the Impressionist artists of the late 19th century by introducing a strong concern for the precise assessment and depiction of natural light through color in the naturalism of the mid-19th century. After spending a year studying Old Master paintings in Italy, Daubigny returned to Paris in 1836 and started producing historical and religious paintings. He initially displayed at the official Salon in 1838, the same year he enrolled in Paul Delaroche’s class at the École des Beaux-Arts.

In his younger years, he had illustrated books. However, his genuine interests lay in the Barbizon school of landscape painting, an unofficial group of artists who defied the conventions of traditional landscape painting in favor of working outside, directly in nature. Daubigny painted in the Morvan neighborhood like Camille Corot in 1852 after the two met. Daubigny’s work started to rely on rigid adherence to tonal values strengthened by a subtle but essential minimum of compositional structure. To observe the riverbank and its reflected effects on the water, Daubigny built a floating studio. Even though they were serene and unspectacular, these paintings quickly became popular, and Napoleon III even purchased one in the Spring of 1857. Some of his famous artworks include: The Ponds of Gylieu, Springtime (1857), in the Louvre, and Morvan (1864).

Although still restrained, Daubigny’s work later in the 1850s started to reflect more intimate poetry. In order to create the illusion of space, he used graded light reflections from surfaces more frequently. These techniques were also intended to provide a fleeting image of the countryside.

Despite being a member of the Barbizon school, Daubigny never really resided there. He is best understood as a bridge between Corot’s more classically ordered naturalism and his youthful companions Claude Monet and Alfred Sisley’s less formal visual receptivity.

Jules Dupré

Born: April 5, 1811 Nantes

Died: October 6, 1889 (aged 78)

Nationality: French

French painter Jules Dupré is most known for his dramatic landscape paintings, which often feature the limited woodland areas surrounding Paris and the choppy Normandy shoreline. He was born in Nantes, France, and began painting porcelain in factories when he was 12. After that, he moved to Paris to work with the painter Jean-Michel Diebolt. When Dupré first came to Paris in 1831, he debuted seven paintings at the Salon, including landscapes of the Haute-Vienne, Montmorency, and a vista of L’Isle-Adam.

Dupré didn’t have any professional training when he first started his career; instead, he honed his skills by copying the landscape paintings of well-known artists like Claude Lorrain and John Constable. John Constable’s landscapes taught him how to express movement in the natural world. At 20, the artist made his Salon debut in 1831 and rapidly attained widespread acclaim. Clarence Cook, a contemporary art critic, said that Dupré’s paintings were rural poems, inspiring peaceful, joyful ideas and that they earned him a warm place in the public heart from the outset.

Constant Troyon

Born: Aug. 28, 1810 Sèvres (in southwest suburb of Paris), France

Died: Feb. 21, 1865 Paris, France

Nationality: French

The father of Constant Troyon worked as a porcelain producer. He loved making good use of his innate artistic drive in his early years, which enabled his career as an artist to advance rapidly.

Inspiration from other painters who are accomplished is always useful in the world of the arts. After understanding this, Constant made friends with Camille Roqueplan, an artist eight years his senior, giving him useful artistic advice. Troyon tried to emulate Camille in some of his early pieces.

His actual artistic nature did not begin to show through until after he relocated to Hague, Netherlands. He concluded that he could produce much better results using animal paintings than landscape paintings and hence he established himself amongst the landscape painters. As soon as he understood this, his renown began spreading worldwide, beginning in the US and the UK.

Many art enthusiasts are still in awe of Constant Troyon’s distinctive brushstroke abilities today. He possessed exceptional color blending and picture harmonization abilities, which gave the bulk of his animal paintings an unbreakable sense of peace and coexistence. He is a well-known historical painter whose paintings are renowned for his wonderful ability to add a sense of realism. Troyon never let a single thing be up in the air. The La Vallee, La plage a Trouville, Cattle drinking, and Cow grazing paintings are among his best and most well-known works.

Constant Troyon was honored with the Legion of Honour award, one of the most prestigious honors in the realm of fine arts, due to his unquenchable need for high-caliber artistic creations. Napoleon III was one of the noteworthy people to express their ardent support for his achievements.

Charles Jacque

Born: May 23, 1813

Died: May 7, 1894 (aged 80)

Nationality: French

Charles-Émile Jacque is a representative of the accomplishments of an artist who made his most significant impact with his engravings, etchings, and lithographs. Jacque was a member of the Barbizon group, a group of artists whose iconography centered on depicting the natural landscape and animals. He was a key figure in the creation of the “Men of 1830” (also known as the Ecole Francaise du Paysage), a loose association of artists that sought out new approaches to landscape painting in the wake of the Revolution of 1830. One of the movement’s most unified and significant collections of art is comprised of his powerful, realistic, yet compassionate depictions of shepherds and their animals.

Charles Jacque consistently entered works into the French salons throughout his career, as well as regional and international shows in Bordeaux, Lyon, Pau, Châlon-Sur-Saône, Munich, London, and even Budapest. In an era and society when painting predominated, his work helped reassess the print’s value. Le Plateau de Belle Croix, Forêt de Fontainebleau (The Plateau of the Belle Croix, Forest of Fontainebleau), an etched replica of a painting by Théodore Rousseau, was Charles Jacque’s entry for his debut at the Salon of 1844. He also started working on his first paintings that year, significantly extending his artistic diversity. He presented a Rembrandt-inspired portrait to the Salon in 1845. His major artworks included: Flock of Sheep at the End of a Wood (1877), Woman Feeding Six Pigs (1850) and Scullery Maid (1844).

Charles Jacque distinguished himself from his peers and even his Barbizon coworkers throughout his life and career. He had little formal training in the arts when he started his career as an artist. Still, he advanced from being a respected illustrator and caricaturist to a respected artist of the “high” arts. He also strongly believed in the value of developing a deep understanding of his subject matter beyond simple observation. But most importantly, he distinguished himself as both a painter and an etcher, helping to bring back the graphic arts as an important art form. However, the lack of extensive training would prevent him from launching a career in the arts immediately. It may have also influenced his choice of the medium because a career in the graphic arts was less expensive and unquestionably less prestigious than one in painting. Each of these facets of Jacque’s career helps to clarify where he fits and how significant he is in the history of late nineteenth-century painting.

Narcisse Virgilio Díaz

Born: 20 August 1807 Bordeaux

Died: 18 November 1876

Nationality: French-Spanish

Narcisse-Virgile Diaz de la Peña was a French painter and lithographer renowned for his numerous romantic portrayals of the Fontainebleau forest and his fantasy landscape paintings with legendary beings.

At 15, Narcisse-Virgile Diaz started working for the Sèvres porcelain factory as a ceramic painter. For a while, he pursued his studies under academic painter Alexandre Cabanel. Early in his career, he frequently painted exotic subjects, heavily influenced by Delacroix and the Romantics and drawn to the Middle Eastern and medieval arts.

With “Scene of Love,” he made his public debut at the Paris Salon in 1831. He occasionally resided in the Forest of Fontainebleau starting in the middle of the 1830s and was highly influenced by Théodore Rousseau. He was also inspired by the beautiful landscapes of the eighteenth century, and he frequently included musicians, peasants, and gypsies in his landscapes.

Diaz started doing landscape paintings in the Fontainebleau forest, close to Barbizon, around 1840. These landscapes, which predominated his output for the remainder of his career, feature a recurrent impression of the dark solitude of the forest, such as in Forest Scene (1867). Spots of light or bits of sky shining through the branches pierce the dense, vibrant greenery. Diaz rarely displayed his work in public during the last 15 years of his life. The Impressionists, especially Renoir, whom he met in 1861 while painting at Barbizon, benefited from his assistance and sympathy.

Barbizon School Artwork

Major artworks in the Barbizon School art movement include: A Meadow Bordered by Trees, The sower, Ville-d’Avray and The Gleaners.

The Gleaners

Artist: Jean-François Millet

Year: ca. 1857

Medium Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 83.8 cm × 111.8 cm (33 in × 44 in)

Location Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Being of Jean-François Millet’s most well-known works, this painting epitomizes the Realist emphasis he gave to the Barbizon School. The artist frequently noticed images of gleaning while strolling through the fields near Barbizon. This was a traditional method of gathering leftover crops from areas that had been harvested. Due to the legal protection of the right to glean, disadvantaged families could supplement their frequently limited diets.

The paintings’s background displays evidence of the plentiful harvest. A shimmering golden haze separates these images of abundance and, in the case of the steward, social status from the poverty of the ladies by surrounding the horse-drawn cart loaded with wheat, the group of harvesters making their way home, and the steward riding a horse. On the other hand, the women are rendered faceless due to the foreground’s dark, repeated shadows covering their features. Due to this contrast between wealth and poverty, as well as between the natural beauty of the fields and the torn, work-worn women, a striking social commentary is produced.

The piece was accepted into the Salon, where it received a lot of disparate feedback. Others attacked it for its realism, horror, and social radicalism, tying it to the rising socialist groups and serving as an unsettling reminder of the Revolutions of 1848. Some applauded it for its dignified picture of the rural poor. Since canvases of large had historically only been utilized for religious or mythological subject matter, Millet’s portrayal of impoverished women was not considered a relevant topic for the scale, contributing to the painting’s condemnation.

A Meadow Bordered by Trees

Artist: Théodore Rousseau

Year: 1845

Medium: Oil on wood

Dimensions: 16 3/8 x 24 3/8 in. (41.6 x 61.9 cm)

Théodore Rousseau frequently went on drawing excursions throughout the French regions. He traveled to the southwest’s Landes region in 1844 with fellow landscapist Jules Dupré, creating works characterized by their keen observation and meticulous execution. This art was most likely painted soon after, in or around 1845. Rousseau used a compositional technique he called “planimetric” to arrange the distant surfaces in parallel strips, as he did in several of his landscape paintings from the mid-1840s.

With a mature understanding of current debates around artists’ mimetic vs. creative abilities, in this painting, Theodore Rousseau blended objective naturalism and his artistic subjectivity to bring out an awe-inspiring landscape genre painting to fulfill his artist’s essential role.

The Sower

Artist: Jean-François Millet

Year 1847-1848

Type Oil painting on canvas

Dimensions: 95.3 x 61.3 cm

Location: National Museum Wales, National Museum Cardiff

The Sower (1847-1848) is a preliminary version of the painting of a peasant reaping that made Millet famous at the Salon in 1850–1851. In what appears to be winter, the artwork shows a peasant sowing on his own property. It is morning because the Sun is shining at the top of the picture. The sower is in the act of sowing his crops with his right hand and is wearing a typical peasant’s outfit, with his legs draped in straw to provide more warmth, striding with large strides, and carrying a bag of seeds over his shoulder. The sower, in this instance, is a shaky figure engulfed by his environment, his seed in danger from ravenous birds. Two grazing animals can be seen in the distance.

The peninsula of Cherbourg, where Millet was born, has a rugged topography. This dramatic scenario depicts an oppressed socioeconomic class and is reminiscent of the biblical tale. In 1911, Gwendoline Davies bought it. The picture is a realistic representation of the tenacity and hard life of the peasant.

Le Semeur

Artist: Jean-François Millet

Year 1850

Type Oil painting on canvas

Dimensions: 101.6 cm × 82.6 cm (40.0 in × 32.5 in)

Location Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In the front of the painting, a man walking long-legged and carrying a bag of seeds across his chest scatters handfuls with his right arm. A man is plowing the ground with his team of oxen while a flock of crows—adequately termed as a “murder”—circle behind him on the left and are highlighted in the distance on the right.

By the time Millet finished this piece, he had already left the politically turbulent city of Paris and relocated to the nearby hamlet of Barbizon. While his Barbizon School contemporaries focused on the scenery, particularly the forests, Millet concentrated on the human figure, frequently a rural laborer alone in the fields, distinguishing his work from that of his contemporaries.

Despite Millet’s extensive use of shadow, the figure stands out sharply against the background of earth tones thanks to his use of primary colors. Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael Sanzio, two of the greatest renaissance masters, frequently employed this technique and found it highly effective. The abundance of dynamic angles that extend outward from the painting’s primary figure emphasizes the sense of intense movement in the piece. The little, faintly depicted figure tilts back while moving downhill, its angular line highlighting the motion even more. The foreground’s shadowiness is underscored by the setting sun’s position behind the Sower. He is an “everyman” attempting to flee the approaching darkness because his hat hides his eyes, his clothing is stained from his labors, and the crows are chasing after him, gobbling up the seeds and ruining his efforts.

Ville-d’Avray

Artist: Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

Year: 1865

Medium Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 65 cm × 49 cm (26 in × 19 in)

Location: National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Ville-d’Avray, is a horizontal landscape painting. We look across a tranquil body of water to a group of cream-white buildings on the far shore from a grassy embankment. The picture has been painted using blending techniques, giving it a hazy and soft appearance. Dots of canary yellow, sky blue, and white indicate that flowers are sprouting on the lush embankment closest to us. Two trees with ash-brown trunks and soft sage-green canopies are located closer to the lake. A fair-skinned woman with a bundle on her back stands by the lake to our left of the woods. She is decked out in an apron, a shin-length dress, and a straw-yellow cap. A second person sits to our right of the trees, looking away from us, sporting a blue shirt and a yellow hat. The structures and trees along the far bank are reflected in the light blue lake.

The villa consists of several connected structures with rectangular windows and charcoal-gray roofs with shallow gables. To our right, tucked into the complex’s surrounding trees, is one more building. At least three persons are standing or walking along the far side, and their clothing is painted with a few strokes of ocean blue, gray, or soft yellow. The forest extends to a third of the canvas’s height where the horizon begins. Several little, puffy white clouds are gliding across the vast blue sky. The artist inscribed “Corot” in black letters in the bottom left corner.

The painting shows a calm lake, buildings on the distant shore, and figures of peasants engaged in their typical, everyday occupations while blending with the surroundings. One of the artist’s favorite subjects, trees, is placed in the forefront. These are probably willows, which Corot frequently included in his paintings. This landscape’s soft pastel tones produce an oddly dreamy early morning atmosphere. The cottages are reflected in the lake, the silver sky is pale, and the light shines on them in a way that is evocative of Corot’s idyllic Italian sketches. Although the elements in the painting are relatively ordinary, Corot manages to make the viewer feel at rest and content. At the same time, the abundance of light and air creates a sense of elegant decay in nature.

Barbizon School vs. Impressionism

Barbizon School and impressionism are significant movements in art history. The Barbizon school operated roughly between 1830 and 1870. It is characterized by tonal qualities, color, loose brushwork, and gentleness of form. It derives its name from the French village of Barbizon, situated on the border of the Forest of Fontainebleau and served as a meeting place for numerous artists. Impressionism was an art movement lasting from 1876 to 1886 and characterized by relatively thin, visible brushstrokes, an open composition, a focus on accurately capturing the changing qualities of light (often emphasizing how time has passed), commonplace subjects, unusual viewing angles, and the inclusion of movement as a crucial component of human experience and perception.

Barbizon School painters included Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Charles Jacque, Jules Dupre, Jean-François Millet, and Charles François Daubigny. On the other hand, early impressionist painters included Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, Mary Cassatt, Vincent Van Gogh, and Edgar Degas.

Impressionism focused on capturing the finer details of nature, such as tree leaves, moss, and pebbles. Unlike Barbizon painters, Impressionists paid more attention to the effects of the light passing through the tree leaves than the actual leaves. One illustration is Monet’s The Bodmer Oak (from the Met), which has light paint touches and less-detailed trees but still captures the lighting effects of the trees. Impressionists rejected classical subjects and accepted modernity. They sought to produce works to record modern life in meticulous detail that mirrored the society in which they lived.

What Art Movements Influenced the Barbizon School?

The Romantic movement’s quest for serenity in nature inspired the Barbizon School of art. However, the Barbizon artists rejected the theatrical picturesqueness of established Romantic landscape painters and the classical academic tradition, which only employed the landscape as a setting for allegory and historical narrative.

What Art Movements Were Influenced by Barbizon School?

The Barbizon artists influenced the development of Impressionism and Post Impressionism. Renoir, Sisley, and Bazille were the students that the artist Charles Gleyre sent to Barbizon in 1860 to sketch and paint. While working in the forest, Manet also created preparatory studies for his revolutionary Le Déjeuner Sur l’Herbe (1863). They became friends and collaborated with the group’s more experienced artists in Barbizon, adopting their methods for wet-on-wet painting, finishing a piece in a single session, and employing novel synthetic colors. The Forest of Fontainebleau was formally designated as the first “Artistic Reserve” in 1874, recognizing the significance of the location in the growth of modern art.