Divisionism, also known as chromoluminarism, is a artistic style and technique involves the use of separate dots or patches of color that interact with each other optically. It is a distinct style evident in Neo-Impressionist painting. Divisionists felt that by requiring the observer to visually blend colors instead of physically mixing pigments, they were attaining the utmost scientific potential for luminosity and colour effects in visual arts.

Divisionism, also known as chromoluminarism, is a artistic style and technique involves the use of separate dots or patches of color that interact with each other optically. It is a distinct style evident in Neo-Impressionist painting. Divisionists felt that by requiring the observer to visually blend colors instead of physically mixing pigments, they were attaining the utmost scientific potential for luminosity and colour effects in visual arts.

Neo-Impressionist artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac adhered to the principles of contemporary color theory. They strategically placed contrasting bits of color next to one other, which, when viewed from a distance, would merge together and be interpreted by the retina as a radiant entirety.

Georges Seurat is recognized as the pioneer of Divisionism in 1884, although he was not the initial artist to employ the Divisionist style. Previous Impressionist artists such as Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet had already found that they might enhance the luminosity of their paintings by employing short, tight brush strokes and by juxtaposing specific complementary colors.

George Seurat established his reputation by methodically studying the techniques employed by the Impressionists. Seeking a distinctive approach to painting that could be regarded his own, he also delved further into the study of color wheel and the works of the Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix, who was celebrated for the brilliant and vivid colors of his artworks. He also studied a range of literature on color theory from previous eras, specifically The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors (1839) by Michel-Eugène Chevreul and The Grammar of Painting and Engraving (1867) by Charles Blanc. Other prominent artists who incorparated divisionism in thei artworks include Robert Delaunay, Jean Metzinger, Théo van Rysselberghe, Maximilien Luce, and Hippolyte Petitjean.

Divisionism and pointillism are sometimes used interchangeably, although there is a distinction between them. Divisionism primarily refers to the underlying idea, whereas pointillism specifically specifies the painting style used by Seurat and his followers. Notable artworks employing the Divisionist method include: Les Andelys, the Riverbank (1886), The Milliners (1885-1886), The Port of Belle Isle Sur Mer (1897), Belle Île En Mer (1897), and Portrait of a Young Woman (1909).

Divisionism is a painting technique where colors are not pre-mixed, but instead placed next to each other on the canvas such that they blend together visually when viewed. Pointillism is a well-known artistic approach that involves creating pictures with countless small circles or points.

The decline of Divisionism occurred in the early 1910s with the emergence of newer artistic movements. The movement had a significant impact on later artistic forms, particularly shaping the development of art movements Futurism, Fauvism and Cubism. Fauvism embraced the vibrant color approaches of Divisionism, while Cubism integrated its systematic approach to deconstructing forms into separate pieces.

Optical Theory Behind Divisionism

Divisionism is a technique that was founded on the idea that colors can be divided into discrete dots or strokes of pure color, rather than being mixed together on a palette. When observed from a distance, the dots merge together in the viewer’s eye, resulting in a more brilliant and vivid effect than when pigments are mixed in the usual way.

Georges Seurat’s chromoluminarism was initially influenced by Charles Blanc’s book, Grammaire des Arts du Dessin. Blanc explained that optical mixing, or mixing colors with the viewer’s eyes, produced more vibrant and pure color effects than the conventional method of pre-mixing pigments before applying them to the canvas. Blanc also drew inspiration from the theories of the great French painter Eugene Delacroix and the French chemist Chevreul. In his treatise “The Law of Simultaneous Colour Contrast” (1839), Chevreul himself asserted that the principle of pure colour over-mixing, where all other colors can be produced by combining primary colors, is applicable to both the combination of light colours (additive mixing) and the combination of colored pigments (subtractive mixing). Our current understanding is that this claim is largely false.

Georges Seurat’s dots of pure color did not merge in the viewer’s eye, but they did create a shimmering appearance and a small enhancement of color. This phenomenon was described in Modern Chromatics (1879) by Ogden Rood. Notably, based on the collections in Paris and London, Divisionist paintings demonstrate exceptional durability in terms of color and composition.

Divisionism vs. Pointillism

Divisionism refers to this division of color and its optical effects, whereas Pointillism is the term used to describe the process of applying dots of color. Divisionism does not necessarily rely on the “dots” that pointillism does, and could instead use tiny brushstrokes of pure color. Divisionism and Pointillism are often used interchangeably, as their differences are subtle.

Characteristics of Divisionism Art

The major characteristics of Divisionism art are scientific approach, optical color mixing and vibrant luminosity. See below for an explanation of each:

Scientific Approach

Divisionist artists were greatly influenced by scientific theories regarding color perception. Applying the colors separately carefully onto the canvas led to a more intense color (as per the theory), and the outcome was believed to be less dull compared to if the colors had been mixed in the traditional manner on an artist’s palette. Painting a Divisionist artwork using dots or distinct brushstrokes required a great deal of discipline and attention to detail.

Divisionism is founded on scientific theories of color and perception, including those put out by Michel Eugène Chevreul, a scientist who examined the optical properties of adjacent colors.

Optical Color Mixing

Optical color mixing occurs when a viewer’s perception of color in an image is influenced by the presence optical mixture of two or more colors that are positioned in close proximity to each other.The apparent color is not naturally present on the surface.However, the color that the observer perceives is determined by the combination of the colors present on the surface.

Divisionism is based on the theory of optical color blending, where small, separate dots or patches of pure color are applied in close to each other. When observed from afar, the viewer’s eye merges these colors, resulting in the intended colour and brightness.

Vibrant Luminosity

The significance of light was paramount among the painters who embraced the divisionist approach, as well as its impressionist predecessors. While the impressionists sought to capture the authentic natural essence of light by painting outdoors (Plein air painting), neo-impressionist artists frequently worked in their studios, employing a scientific approach to organizing colors on canvas.

Divisionism seeks to attain a heightened level of luminosity and vibrancy in paintings by bypassing the monotony that might arise from physically mixing pigments. The colors seem deeper and more vivid. The artwork is more realistic and dynamic because pure, unmixed colors are better at capturing the effects of natural light.

History of Divisionism

Divisionism, a technique of placing individual dots of pure color on a canvas in a way that creates the illusion of combining and enhances the brightness of the colors, was initially developed by Impressionist artists such as Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903). They utilized this technique as one of their instinctive painting methods to capture the transient colors that are present in the reflection of sunlight. However, it was not until 1880 that Georges Seurat initiated a study of technical treatises on color theory in painting, specifically focusing on chromoluminarism and optics. He deliberately undertook the task of scientifically creating the kind of shimmering color effects that artists like Monet had previously achieved through chance and inspiration. This marked a significant advancement in systematic progress.

In contrast to the Impressionists, who mostly employed plein air painting to depict the fleeting qualities of light, Seurat mainly executed his artwork within the confines of his studio, carefully planning every aspect in advance.

The origins of Divisionism, as well as the broader Neo-Impressionism style, can be traced back to Georges Seurat’s renowned artwork, “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.” Seurat underwent formal instruction at the École des Beaux-Arts, which influenced his early artworks to exhibit the Barbizon style. In 1883, Seurat and his colleagues initiated an exploration of techniques to effectively convey a maximum amount of colored light anywhere on the painting. In 1884, the artist showcased his first significant artwork, “Bathing at Asnières,” along with smaller paintings of the island of La Grande Jatte. These works demonstrated his growing familiarity with Impressionism which used more precise geometric shapes. However, it was not until 1886, when he completed “La Grande Jatte,” that he fully developed his theory of chromoluminarism. Initially, La Grande Jatte was not painted in the Divisionist style. However, the artist later modified the famous painting during the winter of 1885-86. He improved its optical characteristics based on his understanding of scientific ideas on color and light.

The theories of Georges Seurat captivated other painters of his time, as they sought to counter the influence of Impressionism by joining the Neo-Impressionist movement. Paul Signac emerged as a prominent advocate of divisionist philosophy, particularly following Seurat’s demise in 1891. Signac’s book, titled D’Eugène Delacroix au Néo-Impressionnisme, was released in 1899 and is credited with introducing Divisionism. It is widely regarded as the definitive manifesto of the Neo-Impressionist movement.

French Divisionism

French painters such as Camille Pissarro, Lucien Pissarro, Charles Angrand, Albert Dubois-Pillet, Henri-Edmond Cross, Maximilien Luce,and Hippolyte Petitjean also incorporated Divisionist techniques into their work, often through their involvement in the Société des Artistes Indépendants. Furthermore, Paul Signac’s promotion of Divisionism has had an impact on the artistic creations of Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, and Pablo Picasso.

In 1907, the critic Louis Vauxcelles identified Metzinger and Delaunay as Divisionists who employed sizable, mosaic-like ‘cubes’ to create compact yet profoundly significant artworks. Both painters had pioneered a novel sub-style that held immense importance shortly afterwards in the context of their Cubist artworks.

Italian Divisionism

The impact of Seurat and Signac on certain Italian painters became apparent at the First Triennale in 1891 in Milan. Initiated by Grubicy de Dragon and later formalized by Gaetano Previati in his 1906 work “Principi scientifici del divisionismo,” a group of painters primarily in Northern Italy conducted varying degrees of experimentation with these methods.

Pellizza da Volpedo employed the technique to depict social (and political) themes; Morbelli and Longoni also embraced this approach. Pellizza created several Divisionist paintings, including “Speranze deluse” in 1894 and “Il sole nascente” in 1904. Divisionism garnered significant support in the realm of landscapes, with notable proponents such as Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati, Angelo Morbelli, and Matteo Olivero. Additional artists who embraced the painting genre of subjects were Enrico Lionne, Plinio Nomellini, Giuseppe Cominetti, Rubaldo Merello, Camillo Innocenti, and Arturo Noci. Divisionism exhibited a significant impact on the artistic creations of Futurists Giacomo Balla (Arc Lamp, 1909), Carlo Carrà (Leaving the scene, 1910), Gino Severini (Souvenirs de Voyage, 1911), and Umberto Boccioni (The City Rises, 1910).

Northern European Divisionism

Théo Van Rysselberghe, a Belgian Impressionist, was greatly impressed by Georges Seurat’s masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte when he encountered it in Paris in 1886. He, along with a cohort of other earlier impressionist painters such as Georges Lemmen, Xavier Mellery, Willy Schloback, Henry Clemens van de Velde, Alfred William Finch, and Anna Boch, brought the style to the Belgian art community, imposing a substantial effect. During his trips to Morocco, the artist produced several pointillist landscapes. However, it was his 1888 Portrait of Alice Sethe that became his most iconic and representative work. His influence led to the incorporation of portraiture as a prominent element in Belgian Neo-Impressionism.

Piet Mondrian, Jan Sluijters, and Leo Gestel, all from the Netherlands, pioneered a comparable mosaic-like Divisionist method around 1909. The Futurists subsequently incorporated the style, partially influenced by Gino Severini’s time in Paris from 1907, into their vibrant paintings and sculptures.

Divisionism influence on Futurism

The Italian Futurists were greatly influenced by Georges Seurat’s ability to convey physical movement in his paintings. In 1909, the Futurist Manifesto was released and lauded speed and industry as the epitome of the aesthetically pleasing and innovative characteristics of the emerging contemporary industrial society. The Futurists adopted Seurat’s concepts to develop their own signature style.

In the article “The (R) Evolution of Modern Italian Painting: Divisionism and its Influence on the Futurist Avant-garde” (2017), Hanstein and Chytraeus-Auerbach, state that the Futurists went beyond simply juxtaposing dots of colors or points to achieve optical blending, they extended this idea to include lines, curves, and forms. By painting multiple images of identical forms inside their compositions, they suggested the dynamic motion of machinery, individuals, and animals.

For more info see our full guide on the Futurism Art Movement.

Divisionism Artists

Major Divisionist artists discussed include: Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Théo van Rysselberghe, Maximilien Luce, and Hippolyte Petitjean. See below for more information on these artists:

Georges Seurat

- Artist Name: Georges Seurat

- Born: December 2, 1859, Paris, France

- Died: March 29, 1891, at the age of 31 Paris France

- Most Known Divisionism artworks:

- A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884-1886

- Bathers at Asnières, 1884

- The Lighthouse at Honfleur, 1886

Georges Pierre Seurat was a French artist who belonged to the post-Impressionist movement. He developed the aesthetic position called pointillism and chromoluminarism, and employed conté crayon for creating drawings on textured paper.

Seurat was motivated by a want to move away from Impressionism’s focus on transitory moments and instead depict what he considered to be the fundamental and enduring aspects of life. However, he adopted numerous techniques from Impressionism, including his affinity for contemporary themes and depictions of urban leisure. Additionally, he aimed to avoid solely representing the ‘local’ or surface color of objects, instead striving to capture the full range of colors that interacted to create their visual appearance.

Seurat possessed a unique artistic personality that harmoniously blended seemingly contradictory traits: a heightened and refined sensitivity, alongside a strong inclination towards logical abstraction and a nearly mathematical accuracy of thought.

Despite his innovative techniques, Seurat initially adhered to a conventional and classical style. He considered the subjects of his major paintings to be figures in monumental classical reliefs, following in the footsteps of the great Salon painters, even though the subjects’ subjects were fully modern and characteristically Impressionist: the various urban leisure activities of the working class and the bourgeois.

Seurat’s later works diverged from the serene and dignified classicism of his earlier pieces, such as Bathers at Asnières. Instead, he ventured into a more vibrant and stylized technique, drawing inspiration from completely abstract composition from sources like caricatures and popular posters. These additions offered a significant improvement to his artistic expression, and, in a later period, resulted in him being highly praised by the Surrealists as an unconventional and independent thinker. Generations of conceptual and abstract painters have been influenced by his interest in the science of color and perception, and this effect is still very strong today.

Paul Signac

- Born: 11 November 1863, Paris, France

- Died: 15 August 1935 (aged 71), Paris, France

- Known for: Painting

- Notable artwork:

Paul Signac was a bright, well-read young man who grew up in the bohemian Montmartre neighborhood of Paris. He was greatly influenced by the Impressionists, who were at the forefront of artistic innovation at the time, as well as by contemporary theories on optics and color.

Paul Signac’s artistic approach underwent significant transformation when he assimilated the techniques and philosophies of Neo-Impressionism (sometimes referred to as “Divisionism” and “Pointillism”), which he co-developed alongside Georges Seurat. The swift and diverse brushstrokes characteristic of his Impressionist technique, which aimed to depict the impact of light on things, underwent a transformation into the small and approximately square dots associated with Neo-Impressionism. Signac, Seurat, and their fellow Neo-Impressionists initiated a process within Modernism that involved deconstructing the fundamental and basic elements of a painting. They achieved this by removing color from the objects it represented, which was a significant advancement towards the subsequent abstraction pursued by later painters.

Paul Signac conducted artistic explorations using several artistic mediums. In addition to creating oil paintings and watercolors, he also produced etchings, lithographs, and numerous pen-and-ink sketches consisting of intricate, painstakingly applied dots. His influence on Henri Matisse and André Derain was significant, ultimately shaping the development of Fauvism. Signac himself did not appreciate the style when it initially emerged.

Théo van Rysselberghe

- Born: 23 November 1862 Ghent, Belgium

- Died: 13 December 1926 (aged 64) Saint-Clair, Var, France

- Notable artwork:

- Octave Maus (1885)

- Madame Maus (1890)

Théo van Rysselberghe is a significant person due to his introduction of the Divisionist style, pioneered by Seurat and Signac, in Belgium. He also played a prominent role in the avant-garde Brussels artist group known as “Les XX” (Les Vingt). Les Vingt was founded in 1883 and in 1887 its members arranged a significant exhibition showcasing Neo-Impressionist artists (DeFina, 1985). That is the place where Rysselberghe encountered Signac and the two established a friendship. Rysselberghe had previously encountered Seurat’s artwork in Paris the year before, and during the show, he was starting to explore Impressionist technique and the breakdown of light and color. This led him to choose a vibrant and radiant color scheme. He was greatly affected by Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte (1884–86), which he observed in 1886.

Starting in 1887, van Rysselberghe adopted the Neo-Impressionist style of painting, making him almost the sole artist to utilize this technique in portraiture. Paintings such as Madame Oc. Ghysbrechts, Octave Maus (1885) and Madame Maus (1890) are from approximately the same period.

Theo Van Rysselberghe’s distinctive artistic style was defined by his extraordinary talent for capturing the interaction of light and color through a well organized pattern of dots. He employed a notable method that consisted of employing small, separate brushstrokes. When observed from a distance, these brushstrokes seamlessly merged together to create vivid and radiant compositions. This method enabled him to elicit a perception of depth, ambiance, and motion in his artworks.

Théo van Rysselberghe derived inspiration from several subjects, encompassing landscapes, portraits, still life, and genre situations. The body of his work displays a remarkable range of subjects and reveals his deep understanding of arrangement, color coordination, and the interplay of lighting. Van Rysselberghe’s artworks frequently portrayed ordinary life events, skillfully expressing the core of human sentiment and the transient instances that shape our being.

Maximilien Luce

- Born: 13 March 1858 Paris, France

- Died: 6 February 1941 (aged 82), Paris, France

Maximilien Luce was a renowned French Neo-Impressionist artist celebrated for his mastery in creating paintings, illustrations, and engravings. Luce, a painter, was initially motivated by Impressionism and eventually found inspiration in the Divisionist style of Georges Seurat. Subsequently, he embraced a Pointillist technique in his painting, as demonstrated in his 1895 artwork titled “On the Bank of the Seine at Poissy.”

Following a period of adhering to strict pointillism, Luce transitioned to a more relaxed and tranquil approach, abandoning the rigidity of Neo-Impressionism in favor of late Impressionism.Luce’s affiliation with the Neo-Impressionists also encompassed their political ideology of anarchism, as evidenced by his pictures frequently featured in socialist publications. While Luce was mostly recognized for his portrayal of landscapes, he also often explored political themes in his artwork, showing a strong identification and understanding of the working class.

Maximilien Luce’s approach effectively maintains the brilliance of colors while skillfully depicting the interplay of light and shadow on three-dimensional forms. While residing in Belgium, he played a significant role in promoting the recognition of Neo-Impressionism beyond the borders of France. The majority of his work focused on landscapes, which he painted both in France and overseas.Urban landscapes typically inhabited specific locations, particularly in working-class neighborhoods, and were frequently depicted at night, serving as visual records of the working-class society during that era. The figures he portrays are distinctive characteristics that set him apart from other artists of the Neo Impressionism art movement.

Hippolyte Petitjean

- Artist Name: Hippolyte Petitjean

- Born: 11 September 1854

- Died: 17 September 1929

Hippolyte Petitjean, a Neo-Impressionist, Pointillist painter, began his artistic training in Mâcon at the age of thirteen. In 1872, a bursary enabled him to study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris under Alexandre Cabanel (1823-89). Petitjean made his début at the Paris Salon in 1880 and continued to contribute regularly until 1891.

Petitjean was artistically inspired by his close friendship with the artist Georges Seurat, whom he first met in 1884. By this time, Seurat had endeavored to study theories of perception and color. Petitjean became an enthusiastic advocate of Divisionism and adopted the technique in 1886.

After the birth of his daughter in 1895, he moved to a house, with a studio, in the southern part of Paris and began to work as an art teacher. He turned increasingly to allegorical subjects, though a series of decorative landscape watercolors produced in the years 1910-1912, marked his return to Neo-Impressionism. This is typical of the career long inclinations Petitjean acted upon, in oscillating between Neo-Impressionism and more academic work influenced by Puvis de Chavannes. His reconcilation of modern art and art history and traditional painting can be seen via his considered and carefully rendered landscapes, whereby his subjects do not rely on allegorical or mythological allusion.

Petitjean’s palette was remarkable for its coloristic vibrancy; he applied dabs of paint with rapid, small brushstokes. Though loose, allowing the paper to show through, this network of tiny, tightly juxtaposed dabs of colour gave the effect of layering. The illusion of alternating tints heightens the colouristic richness and brightness of Petitjean’s scenes. The result obtained from this Neo-Impressionist technique, is a unique ‘coloured light’ which enhances the liveliness of these compositions.

Divisionism Artwork

Notable Divisionism artworks discussed include: Les Andelys, the Riverbank (1886), The Milliners (1885-1886), The Port of Belle Isle Sur Mer (1897), Belle Île En Mer (1897), and Portrait of a Young Woman (1909).

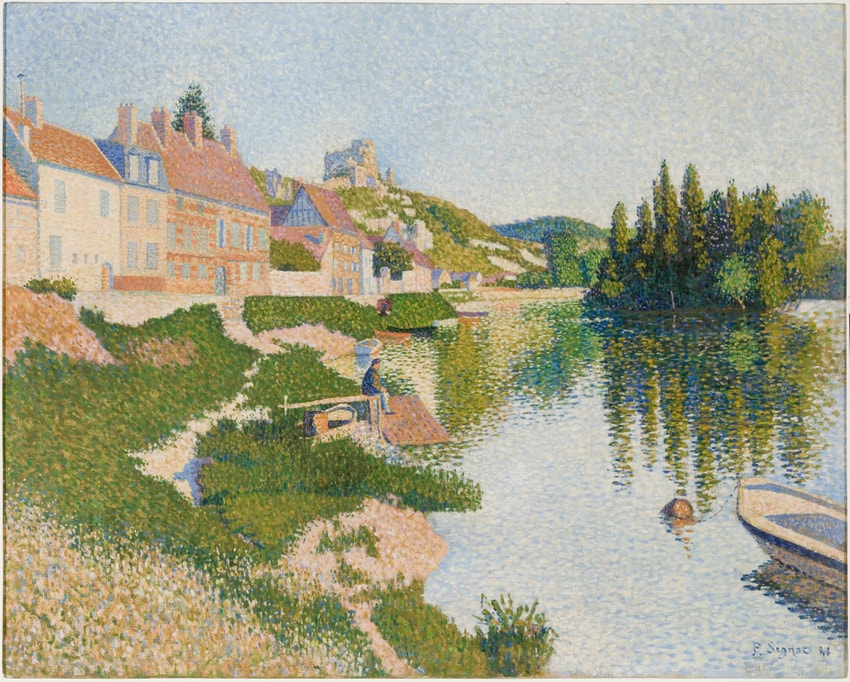

Les Andelys, the Riverbank (1886)

- Artwork Name: Les Andelys, the Riverbank

- Artist Name: Paul Signac

- Date: 1886

- Medium: Oil on Canvas

- Dimensions: 65.3 cm x 81.5 cm

- Current Location: Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France

Les Andelys, the Riverbank portrays a tranquil riverfront setting in Les Andelys. A sequence of picturesque buildings with red-tiled roofs extends along the riverfront, leading up to a hill adorned with the remains of what appears to be a castle or fortification. The calm water mirrors the adjacent vegetation and structures. A person is sitting on a tiny wooden pier at the front of the scene, appearing to be involved in a calm activity, which brings a human presence to the tranquil scenery. The use of pointillism is apparent in the careful implementation of small, discrete dots of color that combine optically, creating a radiant and animated arrangement.

The Milliners

- Artwork Name: The Milliners

- Artist Name: Paul Signac

- Date: 1885-1886

- Medium: Oil on Canvas

- Dimensions: 116 x 89 cm

- Current Location: Emil Bührle Collection

Paul Signac’s early investigation with divisionism is evident in this artwork, which is distinguished by the precise application of small, distinct dots of color.

The Milliners portrays two women deeply absorbed in their craft of making and embellishing hats. The woman positioned on the left is leaning forward, holding a pair of scissors, as she cuts a roll of cloth. Meanwhile, the woman situated on the right is sat at a table, concentrating on making a hat. The table is adorned with a variety of supplies, such as rolls of fabric, ribbons, and hat-making tools. The intricate patterns and vivid hues emphasize the laborious and arduous process involved in their artistry. The background features a wallpaper adorned with a delicate floral motif, enhancing the cozy and personal ambiance of the workshop.

The Port of Belle Isle Sur Mer

- Artwork Name: Port of Belle Isle Sur Mer

- Artist: Henri Matisse

- Date: 1897

The Port of Belle Isle Sur Mer portrays a lively coastal panorama, allegedly capturing the whole essence of Belle Isle Sur Mer. Matisse employed a vibrant range of colors, applied with precise and energetic brushstrokes, resulting in a landscape that possesses a dynamic and slightly fractured aspect, a hallmark of the Divisionist approach. The focus on the segregation of colors corresponds to the Divisionist technique, in which neighboring hues are positioned in close proximity to create optical interactions on the viewer’s retina, rather than being mixed on the palette or canvas. The quayside is teeming with animated figures, evoking the daily hustle and bustle of life by the sea.

The Port of Belle Isle Sur Mer’s composition skillfully guides the viewer’s gaze across the harbor using broad horizontal and diagonal lines, creating a perception of depth and motion. The serene colors of the lake, ranging from blues to greens, create a striking juxtaposition with the warmer tones employed in the depiction of the land and architecture, effectively portraying the harmonious interaction between nature and human intervention. The manipulation of light and shadow enhances the landscape, producing a rhythmic harmony that resonates throughout the piece.

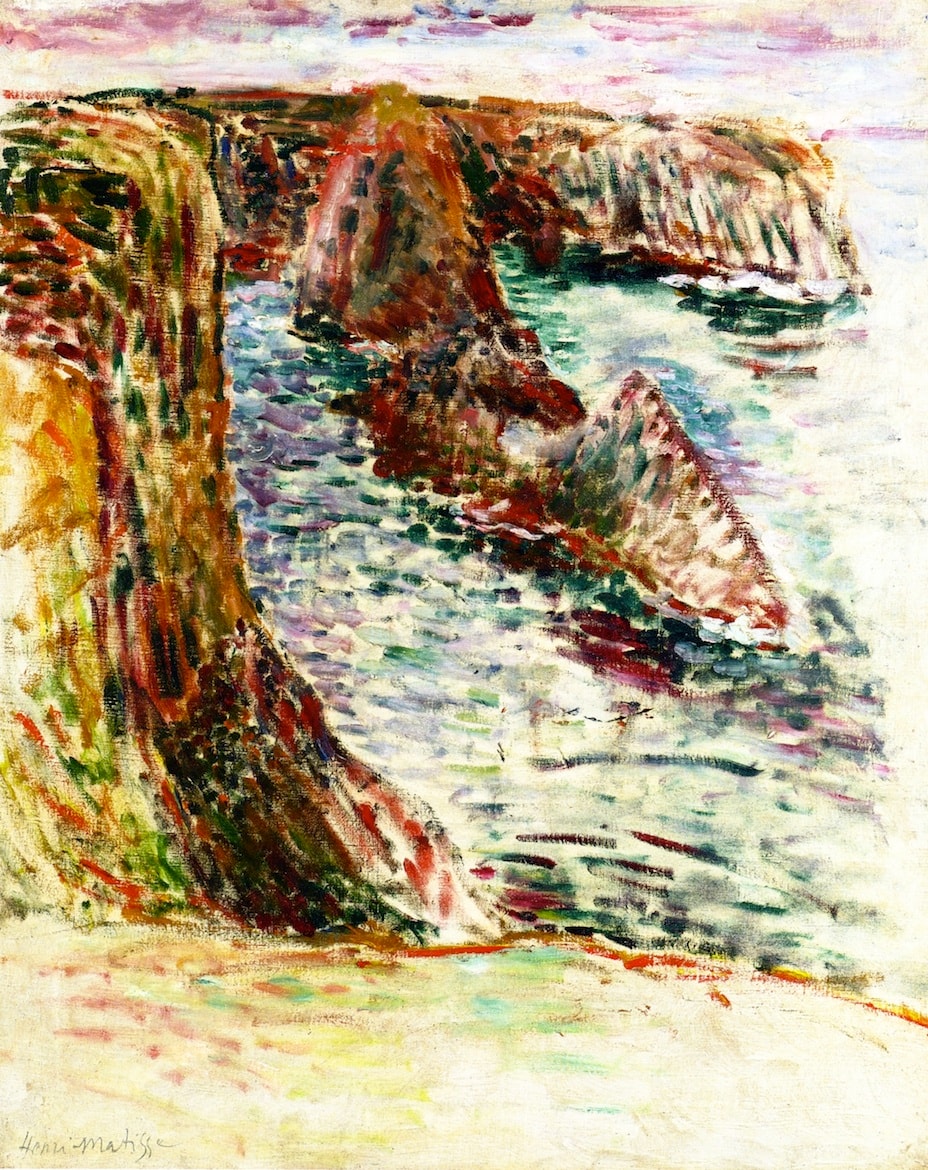

Belle Île En Mer

- Artwork Name: Belle Île En Mer

- Artist: Henri Matisse

- Date: 1897

Belle Île En Mer exhibits Matisse’s initial exploration with color and light, which are distinctive features of the artistic movements that affected him at that time. The artwork portrays a rough coastal landscape with a vibrant interaction of illumination and colors. The brushwork is evident and utilizes a diverse range of strokes to depict the texture and shape of the cliffs and the ocean. The artwork prominently features the juxtaposition of opposing colors, a technique inspired by Divisionism that intensifies the liveliness of the scene. The ocean is depicted with a pattern of blue and green strokes, symbolizing the motion of the waves. The sky above is adorned with shades of pink and blue, indicating either the early morning or late evening.

The cliffs, which are the main focus of the artwork, are depicted using strong and natural colors, characterized by shades of red and brown. The interplay of light and shadow creates the perception of the sun’s brightness on different colours of the landscape. In addition, Matisse’s use of color in distinct yet neighboring sections demonstrates the influence of Neo-Impressionism. This technique enables the viewer’s eyes to blend the colors when seen from a distance, resulting in a radiant impression.

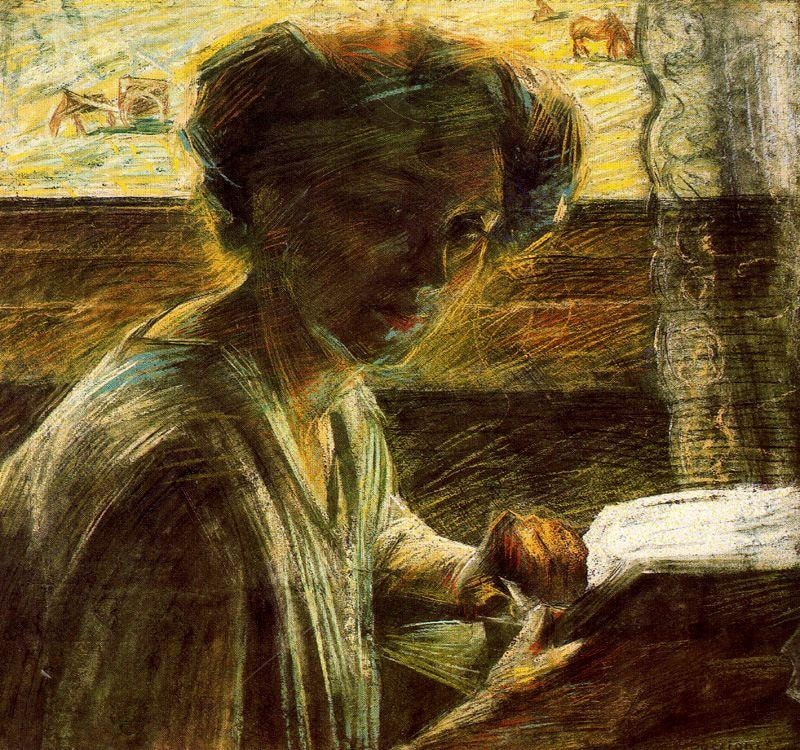

Portrait of a Young Woman

- Artwork Name: Portrait of a Young Woman

- Artist: Umberto Boccioni

- Date: 1909

- Medium: Pastel on Paper

- Dimensions: 54 x 58.1 cm

- Current Location: Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna

Portrait of a Young Woman depicts a young lady with a kind look who appears to be working on something in front of her. Boccioni’s use of the pastel media has allowed him to achieve brilliant color layers with tight, fluid brushstrokes that provide both luminosity and substance (Shrier, 2019). Her delicately defined features convey a close relationship with the observer. The background behind her is abstracted, resembling a room that stretches into space through brushstrokes that accentuate the main figure. The subtle interplay of light and shadow heightens the impression of three dimensions, showcasing Boccioni’s ability to convey depth via color and tone as opposed to the Divisionist style’s signature distinct line work. The background appears to have elements of domesticity, possibly a window looking out into a more open and brightly lit area outside, which invites the observer to consider the subject’s home environment in contrast to the outside world.

Portrait of a Young Woman as a self portrait illustrates the impact of Divisionism, an art movement that distinguishes itself from other formal elements by breaking down colors into individual dots or regions that exhibit optical interaction.

References

- DeFina, C. A. (1985). Belgian avant-gardism, 1887-1889: Les Vingt, L’Art Moderne and the utopian vision (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia).

- Hanstein, L., & Chytraeus-Auerbach, I. (2017). The (R) Evolution of Modern Italian Painting: Divisionism and its Influence on the Futurist Avant-garde. International Yearbook of Futurism Studies, 395.

- Shrier, S. (2019). Umberto Boccioni’s States of Mind.